- Home

- Desmond Hall

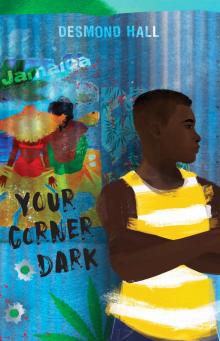

Your Corner Dark Page 2

Your Corner Dark Read online

Page 2

Samson paused, blinked, and then pointed at Frankie’s head. “You need haircut, you know?”

“I’m okay,” Frankie said, shrugging, shifting away.

Samson frowned. “You think since me unemployed, me don’t know how to cut hair anymore?”

“I didn’t say that.”

“So come, mon, bring the chair. Me will give you a proper cut.”

Frankie brushed a hand over his tight curls. Haircuts—his father’s way of making peace. “It’s okay. I’ll get one when I go town.”

Samson folded one hand over the other. “Why you want to spend your money when you don’t have to?”

“It can wait. Besides, you cut the sides too short last time,” Frankie said, thinking this was the moment to draw the line on the beatings. A voice, maybe his mother’s, had always held him back before, counseling him to have patience with his father.

He’s having a rough time at work, Frankie. This too shall pass.

Thing was, things hadn’t worked out for Samson as a short-order cook, a handyman, a barber, or even his brief stint as a boxer. So he never stopped beating Frankie.

When he was little, Frankie had looked at his father’s formidable jaw and imagined that no professional boxer would ever take a shot at it for fear of breaking a hand. But of course one did and had shattered that jaw. Now it looked outsize, not befitting a man of Samson’s height. He was five inches too short for that jaw. And Frankie was too tall for the beatings.

“I think it’s time for the beatings to stop,” Frankie said, all the while wondering how the hell his father would respond.

“Oh?” Samson raised that chin. “You know why me beat you?” He unfolded his hands.

“It’s got to stop,” Frankie repeated, holding his father’s gaze.

“My father beat me till I was—”

“I know. I know. But I’m not you. And I’m not going to take it anymore.” The last sentence took all his courage, he felt almost faint.

“As long as you live under my roof, is me in charge of you.” Samson cracked his neck, left, right. “Frankie, me no love to do it. But until you learn to keep away from trouble—”

Frankie gaped at him. “You don’t think I know that?” Samson was clueless! “I work hard at school. I come in first in all my classes. First! I work hard at my job.”

“And one mistake could take all that away!” Samson roared.

Even though it was only the two of them—had been for three years now—his father didn’t notice anything. It was useless. Frankie turned to walk away and tripped over the molding that ran across the middle of the floor, one of Samson’s makeshift attempts to keep the house together.

In the backyard, humidity was thick, hard to breathe. Frankie pulled his bike away from the pimento tree where it leaned. He’d found the abandoned frame of the ten-speed near his school in Kingston, slowly added parts. After some tinkering, he’d gotten one gear to work. One was enough—he didn’t want to spend the money to fix the other nine. One was enough to get back and forth to where he needed to go.

He straddled the bike, thinking that it was about time to head to school—damn, it was going to hurt sitting in a chair. He stared back at his house, a green-and-yellow box with one back window, a colorful cage that shut out the world. His mother had painted it with so much attention, so careful not to get any of the paint on the window.

He glanced at the neighbor’s house, red and brown, set just past a sprinkling of arching lignum vitae trees and tall beech. Same planking as his. Most of Troy’s houses were made from the wooden storage-room walls of the now defunct sugar factory. At least they weren’t corrugated.

Frankie’s grandfather—a bushman who had harvested what he found in the forests for money—had left Samson the land, but it was Samson himself who had managed to build a house and get actual furniture.

Frankie remembered when, just after his nineth birthday, Samson had brought home an old ham radio that needed fixing. His mother, cancer free back then, had wiped her fingers on her apron, threads dangling from the embroidered roses, and sauntered over to his father. “Our junkyard is looking good. All we need now is a mattress and an old car out front,” she’d said, her voice teasing.

“When me done with this, we’ll be able pick up stations from all over the world,” Samson had replied, spinning a screwdriver into the back plate of the radio.

“I don’t doubt you, but does all the junk in Jamaica need to end up in my house?” She rubbed the tips of her fingers together as if working loose cake batter.

Samson had laughed and dropped the screwdriver, his eyes full of affection.

Frankie dashed over to pick up the screwdriver. He held it to the web of circuits and wires and blew air out of his mouth, emulating the whir of a drill.

“No, mon!” Samson snatched the screwdriver out of Frankie’s hand, pushing him away. “You not learning this line of work. You will do something better.”

His mother had added, “You’re going to college. You will be the first one in the family.” She patted down a fraying rose.

His mother… Frankie blinked away the memory. Blinked at their house—it was a shack, really. He wanted a better place, with more space for his father to live in, a building they could take pride in. You’re going to college. You will be the first one in the family. His mother had outlined the path for a better life, but she hadn’t told him how that path would change other things. He thought of all the hours he had spent hitting the books while his friends ran around in the woods and went on adventures. She also hadn’t told him that he would begin to see the world differently from them. The more he had learned, the more he had drifted, like his genes had transformed. His education had given him some sort of strength, but it was also a weight, a pressure he had to carry that the others didn’t. Things were expected of him now.

Frankie had just placed a foot on the pedal as Samson walked into the yard, shoulders swaying, chin up, carrying the clippers and a white towel.

“Me won’t cut the sides too short this time.” Samson clicked on the clippers. “We got ten minutes before you need to go to school.”

That was as much of an apology as Frankie would get and he wanted it, he did, but he could feel the push, his pride a dam against the words. Still, he hesitated, lowered his foot. The right thing, the practical thing, spun through his gut, fighting the anger he still felt in his head, in his back. An ant was making its way toward his shoe. Frankie watched it for a moment and thought about stomping it… then simply dug his shoe into the dirt and scared it away. He sat up tall on the bike seat. “Okay, you can cut it.”

Samson stretched out the frayed towel, draping it over Frankie’s shoulders.

He rubbed Frankie’s head; his fingers, warmer than the air, hardened by a life of physical labor, dug into Frankie’s temple. Then he leaned in close and began running the clippers away from Frankie’s forehead toward the back of his skull.

“Remember, always cut your hair backward. You want the grain growing out this way.”

How many times had his father said that?

Samson stepped back and squinted at the side of Frankie’s head. He moved forward. The cold steel of the clippers whizzed at the edges of Frankie’s ears.

Straining his neck, but not quite pulling away, Frankie hoped the clippers wouldn’t cut too close.

Three

frankie swung onto Constant Spring Road, passing a Bank of Jamaica and a bus. A dark charcoal stench seeped from the muffler. Frankie caught his reflection in the window of a sneaker store. His school-issue khaki pants looked okay, but his khaki shirt could have used a bit of ironing. Whenever he took his five-mile bike ride to school, which was always, he felt like there was a sticker on his head that said COUNTRY BOY. And the front wheel of his bike was wobbling again. Damn.

Still, every time he passed under the gold crest on the West Kent school gates, he thought of his mother. She’d flat-out beamed when he’d been selected to go to such a prest

igious institution. Our kind of people don’t get many chances like this, boy. Don’t mess it up. He didn’t, but without the scholarship, his mission was incomplete. And at the moment he was feeling down about his chances. Maybe it was the fight with Garnett, or the problems with his father. And what the hell was up with Winston? A gang? He had to talk to him, smack that thought right out of his dumb head.

The guard at the gate nodded as Frankie rode past. Two girls in school-issue white dresses with green belts and loosely fitted neckties also nodded. He didn’t know them, but he waved anyway, not to be a jerk; being a senior had privileges and responsibilities. Still feeling down about the scholarship, he chained his bike at the end of the bike rack. Then he looked up at the two-story admin building. His guidance counselor’s office was in there. She was always so positive—seeing her was like going to a pep rally. He had twenty minutes before his first class, so he decided to go visit.

Scholarship or not, he had to admit he was going to miss this school. He’d worked his butt off and was proud of all he’d achieved. He had to admit that, too. Glancing around quickly to make sure no one was looking, he took hold of the school crest hanging in the foyer and carefully tilted it—it had been carved from thick mahogany several years ago by a group of students who’d also come from less privileged communities. Pulling back, he eyed it, making sure it was straight.

“Hey, Frankie!” It was a guy in his engineering class. “Want to work on the final project this weekend?”

“No, mon, I handed that in like a week ago.”

“But dude, it’s not due for three weeks.”

“Why wait till the last minute?” Frankie grinned. “Likkle later.” As he walked toward Mrs. Gordon’s office, he remembered the crazy number of hours she’d spent with him throughout the entire application process for the scholarship—and she always had something positive to say.

Finally to the end of the corridor, he walked through the large open meeting room and stood outside Mrs. Gordon’s office. She looked up, a big smile spreading across her face as if she was expecting good news. Frankie felt like crap. He couldn’t tell her he was feeling depressed, not now. She was counting on him. He couldn’t let her down by being down. “Not yet, but fingers crossed,” he told her.

She nodded, put down her pen, and crossed fingers on both hands.

Feeling like a total fake, Frankie forced a smile, turned away, and headed toward class.

* * *

Sitting behind the register in Mr. Brown’s store after school, Frankie tried to read the notes he’d taken in statistics class, but his handwriting looked like a fuzz of long straight lines and loopy letters. He gave up and grabbed the issue of Popular Mechanics he’d borrowed from the library the other day. “Tech Wars” was the cover story. He’d read it twice already.

He tossed the magazine on the counter. Man, was he bored. He stood up and stretched, forgetting his back until he felt the sear. Gahhh! He pressed his palms against his eyes until the pain quelled, not wanting to think of that beating. He was forever getting caught up in Winston’s craziness. Then Frankie looked up at the clock—Winston was late. Typical. He said he’d stop by the store to talk. Frankie needed to straighten him out. The thought of Winston in a gang, Winston with a gun, made his gut clench.

And when the heck had Winston even done that? Frankie had pretty much been looking out for him since kindergarten. Two big third-grade girls had been pulling on Winston’s lunch bag, trying to take it from him. If Frankie hadn’t gone over to help, they would have gotten it too. And for a week the girls kept coming back to torment Winston, so Frankie kept coming over to help. It must have been something about the way Winston looked. He was just the type of kid bullies gravitated to.

And if Frankie got the scholarship, he’d be off to America in a matter of months. Who’d keep an eye on Winston, then? Keep Garnett away from him? Garnett. Dude’s face had looked like a hyena’s when he’d pounded on Winston, his lips twisted all nasty. Frankie knew Garnett wouldn’t let it go. Yeah, he had to talk to Winston.

Just beyond the pyramid of yams, dirt still clinging to the roots, Frankie snuck a peek through a partially opened door made of reinforced steel into the storeroom. His boss was hunched over two of the dozens of orange ten-gallon poly bags Frankie had stuffed with marijuana earlier in the week. This was the part of his job he didn’t tell Samson about—the part that made his paycheck more significant than it should have been.

Frankie decided to have some fun. “Need anything, Mr. Brown?”

Mr. Brown flinched, his nostrils flaring. “You interrupted my count, Frankie.” He turned back to his work, this time mouthing the numbers.

Shrugging, Frankie passed the walls of wooden shelves—noticed that the Nescafé and cans of butter beans needed replacing—to the front door. Where the heck was Winston? Just outside, perched on milk crates at a rickety folding table, two old men silently studied snaking lines of dotted ivory.

“Yes now!” one shouted, and slammed down his domino.

“You gimme di game!” The other old-timer wound up like he was going to chop the table in half with the domino in his hand, but at the last minute landed the double four softly as you please. That set off a twister of insults and sharp comments.

Frankie laughed. He hadn’t played dominoes in eons. He remembered a rare late-night domino party in his own backyard. Remembered the pungent flavor of curry goat his mother had made. She had barged her way into the game he was playing with Samson and some of their grown-up friends. “I only know how to match,” his mother had said, as if she were meek and helpless, her doe-like expression all innocent. Frankie couldn’t forget the way Samson’s eyes held her.

The game had become intense, both sides close to reaching the total number of points they needed to win. Frankie’s mother was surveying the tiles, probably counting the matches. Frankie remembered looking at the line of dominoes on the table: the four and two domino matched with the two and the six. He had figured that if his mother had a six in her hand she could play, but if she had a double six, or some other way to block the game so no one else could make a move, she might be able to win, because she had the highest point total. But double six… no way.

Just as he was thinking that, his mother smacked her fist down on the table and slowly opened her hand like a magician. Double six. “I suppose this means I win,” she said, and the tipsy guests exploded with laughter, some shouting loud complaints of clever deception.

The remission was what was truly deceiving. Frankie had thought that remission meant the cancer had been stopped. But little by little it snuck back, ate away at her until it took her life. Watching the old-timers now, Frankie realized that his father hadn’t played dominoes since his mother had died. Damn.

Just then Winston strolled up, looking sheepish.

“You’re late,” Frankie called out. “You said you were coming by forty minutes ago.”

“Me here now, mon,” Winston said, shrugging past him into the store.

Frankie shook his head and followed him in, returning to his spot behind the cash register. Winston began thumbing through Frankie’s statistics book. “Me don’t understand one word in this thing.”

“Maybe you should go back to school—”

“School? That’s for you. Me have to scuffle. Me name ‘Sufferer.’ ”

“What’s my name, then? You see where I work.” Frankie pressed a key on the ancient cash register. He knew it wouldn’t even open.

“You package the ganja for Mr. Brown, though,” Winston countered. “Him pay you extra for that, no true?”

Frankie gave him a cold, blank stare; he’d never told Winston about the side-hustle part of his main hustle. Winston clearly had his ways. But there was one thing Winston didn’t know about. “He let me drive the other day, his van, you know?”

This gave Winston pause. “Brown did? Where?”

“All the way into Kingston.”

“Him was in the van with you?”

“Yeah, but I drove, mon.”

Winston twitched a shoulder, playing it off. “So, what about the foreign t’ing? The scholarship?”

Frankie was as weary of that question as he was of working in the store. “Don’t know yet.” He was so lucky to have gotten into the fancy school. Winston and his other friends had, one by one, dropped out of their dinky high school on the mountain. None of them were graduating. Fact was, Frankie couldn’t stop feeling kinda guilty about it, like he was an imposter or something. Like, why him? How was he worthy of all he’d gotten, and might still get if he actually got the scholarship? Yeah, he’d worked hard, but still. Why him? There were others all over the island, just as deserving, maybe more. Like, why not Winston?

Winston picked at his teeth with his thumbnail, a habit he’d had for forever. Their mothers had become friends when Winston was in second grade, after his father took off. Mamma helped take care of Winston while his mother worked. Winston always piled his plate with more than he could handle, stuffing himself as if the future had no more, his ma used to say. Frankie considered this. Winston always got caught up in saying and doing things that came across as desperate; guy was always trying too hard. He always needed more…. Frankie knew how his psych teacher would describe it—needing to be more than his father was, and at the same time, not worthy, because of his father. And Frankie’s spin on it was, it all made Winston sometimes act like an idiot. Frankie had felt that way about his own father, still did from time to time.

Still, there was no doubting Winston’s friendship. Back in fifth grade, Frankie had been crazy sick with a high fever, the whole town saying prayers for him. Winston had been so freaked out that he had tried to steal a toy car as a gift for Frankie. Of course, Winston being Winston, he got caught. But still. His mamma always said Winston’s heart was in the right place. That had to count for something.

Winston closed Frankie’s textbook. “So, you know you better watch out for Garnett now.” He tapped the counter for emphasis. “You know that, right?”

Your Corner Dark

Your Corner Dark